A blog about Zionism, Jewish identity, and antisemitism.

© 2025 Michael Jacobson. All rights reserved.

For millennia, Jewish men, particularly Torah scholars, have covered their heads and/or necks with a woven cloth called a סודרא (sudra, sudara) or סודר (sudar). Jews in late antiquity routinely wore sudarin, and the garment is consequently mentioned frequently in the Mishnah — a written record of Jewish common law, and daily life in the Land of Israel, compiled in the first two centuries of the Common Era. The Jewish Encyclopedia, published in twelve volumes between 1901 and 1906, explains that ‘[t]he Israelites most probably had a head-dress similar to that worn by the Bedouins … a keffieh folded into a triangle, and placed on the head with the middle ends hanging over the neck to protect it.’

The encyclopedia also says that, in later times, Jews wrapped their headcloths around a small cap ‘to shield the other parts of the head-covering from perspiration.’ Even today, some Yemenite Jewish men still wear sudarin, usually wrapped around a central felt cap called a כומתא (komtah), to form a headdress similar to a turban.

Rabbi Marcus Jastrow’s scholarly Dictionary of the Targumim, the Talmud Babli and Yerushalmi, and the Midrashic Literature, written in the late 19th century, defines sudra as a ‘scarf wound around the head and hanging down over the neck, turban’. Rabbi Ernest Klein’s 1987 Etymological Dictionary of the Hebrew Language defines it as a ‘scarf’ or ‘shawl’. The word itself is Aramaic, but its etymology is disputed. Klein asserts that it is related to the Latin sudarium (handkerchief, napkin), while Jastrow regards the similarity as a coincidence. The Babylonian Talmud, in tractate Shabbat, offers an acronymic etymology, claiming that sudra is an acronym, derived from a biblical verse which states that ‘the counsel of the Lord is with those who fear Him’. While this may seem fanciful, it is certainly in keeping with the known origins of many Jewish words, both classical and modern, as well as the ancient minhag (Jewish custom) of covering one’s head to demonstrate reverence to God.

While the sudra seems to have been primarily worn as a headdress or turban, at times it was also used as a neck scarf. Rabbi Ovadiah Bartenura, in his 15th century commentary to tractate Shabbat in the Mishnah, described the typical weekday attire of a תנא (tanna) — a Jewish sage of the 1st century CE — which included, in addition to a head covering, a ‘sudra on his neck whose two points are hanging in front of him, which is called shid in Arabic.’

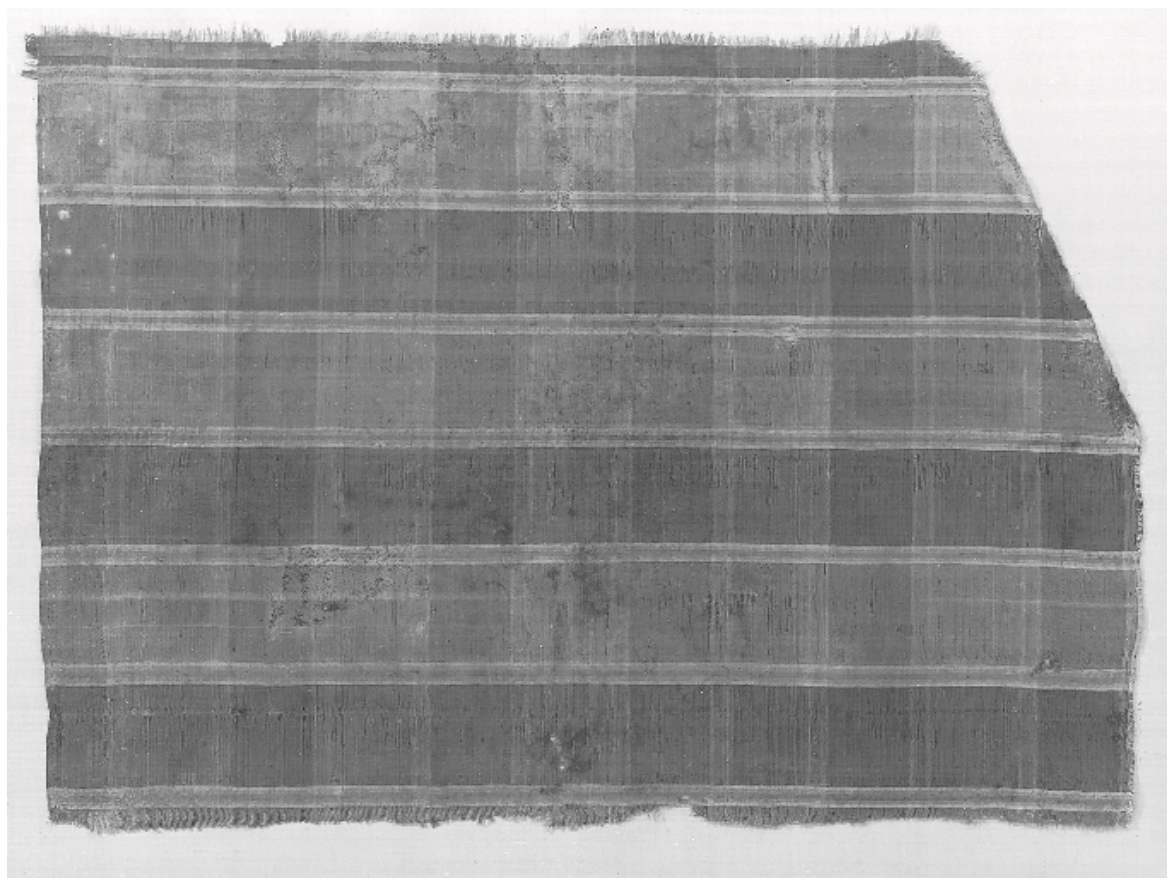

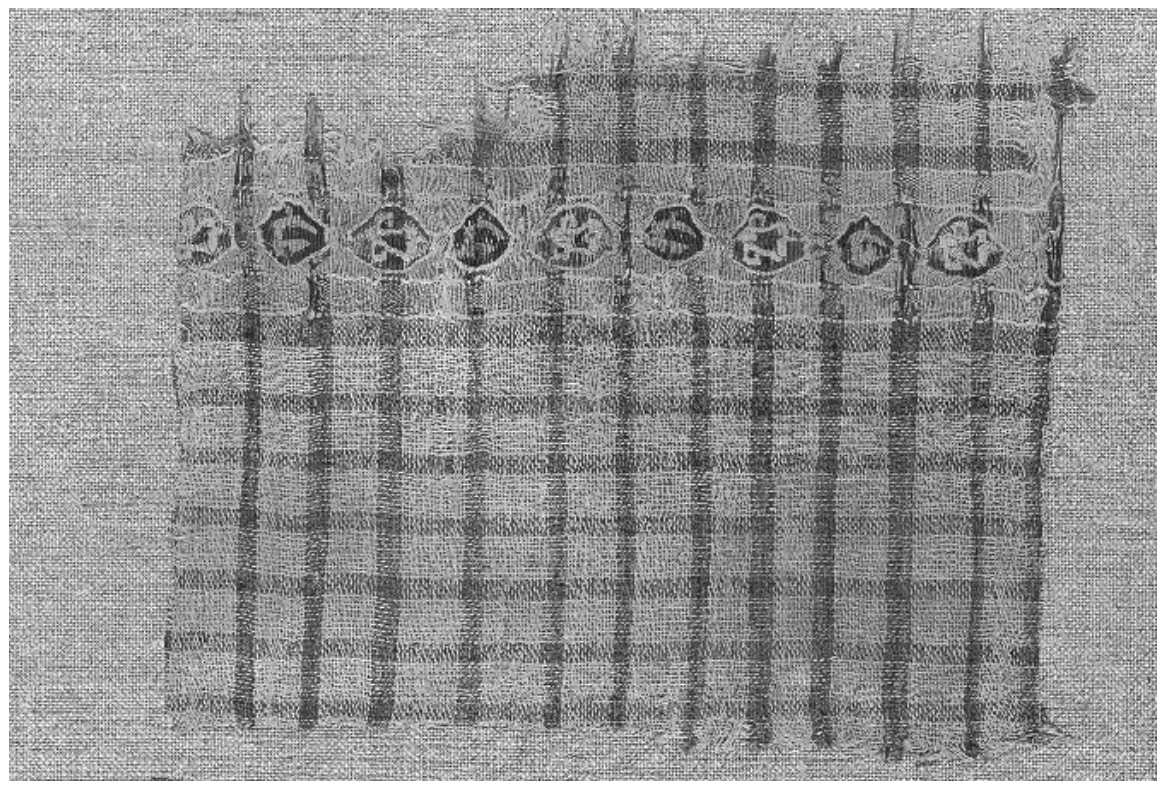

The Mishnah describes a sudra as measuring two cubits (roughly one metre) on each side. Sudarin were probably made from linen, wool, or cotton — historically the most common woven fabrics used by Jews in the Land of Israel. While a mixture of cotton and wool may have been used, shatnez (the non-kosher blend of wool and linen) almost certainly wouldn’t have been. Despite being four-cornered garments, sudarin did not require ritually knotted tzitzit to be attached to their corners. But they may have featured simple fringes or tassels along their edges for aesthetic purposes. Such decorative fringes are often seen on the edges of tallitot (Jewish prayer shawls), whose design is believed to have changed little since antiquity.

Both dyeing and weaving have been mainstays of Middle Eastern Jewish culture and trade for millennia, and Jewish artisans have long been recognised as masters of textile crafts. When Benjamin of Tudela visited Jerusalem in the 12th century, he reported that the Jews of the city held a monopoly on dyeing, as agreed with the then Crusader King Baldwin III. In 1948, after centuries of Islamic persecution, many Yemenite Jews decided to abandon their millennia-old homes and seek refuge in the newly founded State of Israel. The Jewish craftspeople of Yemen, known as particularly adept weavers and silversmiths, were forbidden from leaving the country until they had passed on their skills to local Muslims.

The Cairo Genizah, a veritable treasure-trove of medieval Jewish documents, provides vivid descriptions of Jewish fashions in Egypt under both Fatimid and Ayyubid rule. Yedida Kalfon Stillman — a distinguished ethnologist and expert on the folkways and material culture of the Middle East — wrote extensively about the textile patterns and adornments recorded in the genizah. Stillman reported that clothing was often colourful, and that particularly expensive garments were occasionally embroidered with gold. Coloured fabrics were sometimes ornamented with a border of a different colour, and some had fringed borders. Stripes of various kinds seem to have been popular, including a design with ‘belt-like bands’ and another resembling a pinstripe. Two checkered designs were common at the time — one similar to a modern windowpane pattern, and the other similar to a chessboard. It is likely that many of these styles were represented in the sudarin of medieval Jews.

It is interesting to note that — although credible historical sources regarding their origins are rare — Ashkenazi fur hats such as the shtreimel, and its relatives the kolpik and spodik, may have developed from the sudra. A shtreimel is traditionally made from sable, marten, or fox tails, wrapped around a simple central cap. This cap is typically made from black velvet, and is not unlike the aforementioned komtah, around which Yemenite Jews wrap their sudarin.

A popular story, passed down by Ashkenazim for generations — including the renowned Hasidic scholar Ahron Marcus, the Nobel laureate S. Y. Agnon (Shmuel Yosef Agnon), and Rabbi Yekusiel Yehudah Halberstam, founder of the Klausenburg Hasidic dynasty — recounts that a Jew-hating Polish king once decreed that married Jewish men must wear animal tails affixed to their heads on Shabbat, so as to humiliate them in front of their wives. It is thought that wearing animal tails on one’s clothing was a symbol of ridicule in parts of Europe, as illustrated in Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s 1568 painting, The Beggars. Regardless of whether or not this story is true, it is certainly possible that, over time, Ashkenazi Jews stopped wrapping a woven sudra around their caps, and began wrapping furs instead.

Following the death of Muhammad in 632 CE, Muslim armies marched north — out of the Arabian Peninsula and into the Levant. Within fourteen years they had wrested control of the region from Byzantium (the Eastern Roman Empire, whose capital was Constantinople), and incorporated it into the Caliphate. This marked a profound change for the peoples of the Levant — away from the broadly tolerant and cosmopolitan rule of the Byzantines, and toward a more monolithic one under the Islamic empire.

Prior to the Muslim conquest, most of the region had been ruled continuously for almost seven centuries by the Roman Empires. Latin and Koine Greek were often used for trade, diplomacy, and as linguae francae. But, throughout these centuries, the indigenous peoples continued to speak their native (Northwest Semitic) languages — primarily Hebrew and Aramaic. By contrast, it is estimated that less than a century after the Muslim conquest, almost all peoples in the Levant had been forced to adopt Arabic as their vernacular. The invaders commanded the indigenous pagan tribes of the Levant to submit to Islam or be slaughtered, while Jews and Christians, as Ahl al-Kitāb (Peoples of the Book), were spared death.

Following the Pact of Umar, the conquered Jews and Christians came to be known as dhimmis, and were granted the ostensible ‘protection’ of Islam. Dhimmi communities were required to pay an extortionate poll tax (jizya) each year and, upon delivering the tax money, it was often customary for the head of the Jewish community to be slapped across the face by the local Muslim governor. As dhimmis, Jews (and Christians) were subordinated to Muslims, and had to show deference to them at all times. They were frequently victims of massacres and expulsions by Muslims, but were forbidden to carry weapons for self-defence, and forbidden to ride horses or camels. They were excluded from public office and military service. Their homes and places of worship were not allowed to be taller than those of their Muslim conquerors. Dhimmis were subject to execution if they were found guilty of criticising Islam, or accidentally touching a Muslim woman, but they were not permitted to give evidence in the Islamic courts — even to defend themselves against such allegations. There was a great deal of segregation. For example, Jews were usually only allowed to visit markets at the end of the day, to allow Muslims to get the pick of the produce, and to ensure that any foodstuffs that were ‘contaminated’ (by their proximity to Jews) wouldn’t be purchased by Muslims. Dhimmis were often confined to ghettos, or vulnerable encampments outside city walls.

The clothing of dhimmis was also officially mandated by Muslim rulers; at times they were forbidden from wearing certain garments or colours, and obliged to wear others, simply to humiliate them and reinforce their perceived inferiority to Muslims. As in Christian Europe, Jews were frequently required to wear distinguishing marks or badges, often red or yellow in colour — a policy infamously adopted centuries later by the Nazis. One of the most notable prohibitions was on the wearing of headscarves or turbans which, according to a popular hadith, are the ‘crowns of the Arabs’. Another hadith describes Muhammad as having worn a white silk turban called al-Sib (The Cloud). The Babylonian Talmud, tractate Berakhot — written several centuries before Muhammad’s birth — teaches that upon spreading a sudra on one’s head, one should recite: ‘Blessed are you Lord, our God, King of the Universe, Who crowns Israel with glory’. It is likely that this, or a similar bracha (blessing), was recited daily by the Jewish tribes of the Hejaz, among whom Muhammad lived, and he may well have appropriated and adapted it from them. It is widely accepted that Muhammad’s theology was heavily influenced by Jewish customs, such as ritual circumcision (brit milah, khitan), classification of foods (kosher, halal), and fasting on the tenth day of the calendar year (Yom Kippur, Ashura).

Yedida Stillman explains that ‘[s]omber-colored clothing, black slippers when going shod at all rather than the yellow ones worn by Muslims, dark caps and perhaps a blue headscarf, remained the generally enforced mode of dress for Jews in Morocco’. In Yemen, a late 17th century decree forbade Jews from covering their heads, and officially remained in force until 1872. On at least one occasion, in Eretz Yisrael, Jews were accused of masquerading as Muslims when they covered their heads with traditional prayer shawls that were white, and therefore forbidden to them. Across the Middle East Jews were frequently required to wear yellow, blue, or black garments, and often prohibited from wearing white or green.

Enforcement of the dhimma laws was less than consistent. In certain regions, and under certain governors, the rules were barely noticeable — as evidenced by similarities between Jewish and Muslim dress recorded in the Cairo genizah. At other times they were ruthlessly enforced — Jewish women were being sold as slaves in parts of Muslim North Africa as recently as 1896. During the later years of Ottoman rule in the Levant, the dhimma laws were greatly relaxed, largely as a result of European influence. However, many of the discriminatory rules were subsequently re-introduced by Arab nationalists after the First World War and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. The legal status of Jews as second-class persons (often stripped of their citizenship) continued well into the 20th century in many Arab countries. The thousands of Jews in Syria — where Nazi war criminal Alois Brunner served as an adviser to President Hafez Assad — were brutally persecuted, and effectively held hostage by the state until 1994. Even today, Egypt has a law on its books that allows the state to arbitrarily revoke the citizenship of Jews.

There were periods of toleration, and even relative prosperity, for some dhimmis under Islamic rule. But — prior to the founding of the State of Israel — most Jews, living in their ancestral lands, had spent fourteen centuries being subjugated, demeaned, and persecuted by Muslim conquerors.

If you Google ‘history of the keffiyeh’ today, you’ll find websites such as Hebron Arts and Handmade Palestine, who spin romantic yarns (pun very much intended) about the history of the garment. They claim that keffiyehs evolved from priestly habits worn by Bronze Age Sumerian rulers, but provide nothing to substantiate this theory. Numerous ancient but detailed portrait sculptures have survived, depicting Gudea, a Sumerian leader of the 22nd century BCE, most of which portray him bareheaded. Some of these statues do, however, show him wearing a hat uncannily similar in shape to a modern shtreimel. While amusing, this is of course a complete coincidence.

The next step in the long and storied history of the keffiyeh — according to these accounts — comes almost 5,000 years later, in the early 20th century, when Arab fellaheen (rural farmers, agricultural labourers) wore keffiyehs while working in the fields of Ottoman Palestine. No mention is made of the fact that these fields were likely cultivated by Zionist settlers — in a 1909 letter to his mother, T.E. Lawrence (of Arabia) wrote that ‘Palestine was a decent country then [in Jesus’ time], and could so easily be made so again. The sooner the Jews farm it all the better: their colonies are bright spots in a desert.’

In 1931 British Lieutenant-General John Bagot Glubb, better known as Glubb Pasha (an honorific bestowed upon him by the Bedouin soldiers whom he commanded), founded the Desert Patrol. The Patrol was a semi-autonomous paramilitary branch of the Arab Legion — a force raised by the British in 1923 to maintain order among the disparate Arab tribes of Transjordan. The striking uniform of the Desert Patrol, which was designed by Glubb Pasha himself, included a red-and-white checkered keffiyeh. Most of these uniform scarves were manufactured by British factories, probably in Manchester. Describing the uniform, Glubb later wrote that ‘[t]he headgear was a red-and-white-checkered headcloth, which has since then (and from us [the British]) become a kind of Arab nationalist symbol. Previously, only white headcloths had been worn in Trans-Jordan or Palestine’.

Glubb’s boasting was clearly somewhat hyperbolic, but the overwhelming majority of keffiyehs worn by Palestinians during the British Mandate were plain white, and without fringes. They were generally worn draped over the head and shoulders, and held in place with an agal (a thick cord, typically woven from camel or goat hair). Despite the pattern being an entirely arbitrary aesthetic choice, made by a British colonial in the 1930s, the red checkered keffiyeh remains a symbol of national and military pride in the Kingdom of Jordan today. The same design has also proven immensely popular with the Marxist-Leninist PFLP (Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine).

Izz ad-Din al-Qassam (for whom both Hamas’ military wing and their eponymous artillery rockets are named), was a Syrian Arab who fled to Palestine in the 1920s after being sentenced to death by the French colonial authorities in Damascus. He quickly became a tremendously popular preacher at Haifa’s Masjiid al-Istiqlāl (Freedom Mosque). His fiery sermons — during whose delivery he sometimes brandished a gun or sword — actively encouraged Muslims to take up arms, and wage jihad against the British and the Jews. He was a charismatic leader, and did much to cultivate Islamic political violence in Palestine. It is believed that he had been secretly organising and training cells of guerrilla jihadists, mostly recruited from the rural peasantry of northern Palestine, since the mid-1920s.

In November 1935 Qassam’s guerrillas murdered Police Sergeant Moshe Rosenfeld, and the Palestine Police Force quickly set out to apprehend Sgt. Rosenfeld’s killers. To avoid arrest, Qassam — accompanied by a small handful of his followers — fled Haifa and went to ground in the hills around Jenin and Nablus, where they were fed and sheltered by the local Arab villagers. In a spectacle reminiscent (at least in my mind’s eye) of the climactic final scene in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid — the police manhunt eventually tracked Qassam to the village of Sheikh Zeid, where a large contingent of armed police officers surrounded his hideout. Called upon to surrender, Qassam told his men to die as martyrs, and he opened fire. In the ensuing firefight he, and three of his men, were killed; the remaining five were arrested. The violent ‘last stand’ of Qassam quickly galvanised Palestine’s Arab populace, and more than 3,000 mourners attended his funeral.

Then in April 1936 — less than a year after Hitler’s Reich enacted the Nuremburg Race Laws — the pro-Nazi Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Mohammed Amin al-Husseini, established the Arab Higher Committee, which lobbied the British government to block all Jewish migration into Palestine and prevent the sale of land to Jews. Capitalising on the popular radicalisation fomented by Qassam, as well as the widespread anger at his death in a hail of British bullets, the Committee fanned the flames of an incipient Arab insurgency — the so-called ‘Great Palestinian Revolt’. The revolt lasted until 1939 and involved violent rioting, vandalism, murders, bombings, and general guerrilla warfare. The Arab rioters primarily targeted British officials, and symbols of British colonial rule, but they were not above also massacring Jewish civilians. By the time the revolt ended, at least 400 Jews had been killed; some were Zionist partisans, but many were unarmed non-combatants. Following the uprising, Britain partially acquiesced to the Arab demands, and placed strict quotas on Jewish immigration into its mandate. Vessels from Europe — heaving with emaciated and destitute Jewish refugees, fleeing the Nazi genocide — were turned away from Palestine by the British Royal Navy. Some were subsequently torpedoed and sunk by Italian or German warships.

In 1941 Husseini met with Hitler, and other senior Nazis, to discuss formal Nazi-Arab cooperation. The same year, he requested that the Axis leaders publicly declare that they ‘recognize the right of the Arab countries to solve the question of the Jewish elements which exist in Palestine and in the other Arab countries, as required by the national and ethnic (völkisch) interests of the Arabs, and as the Jewish question was solved in Germany and Italy.’ On 1 March 1944 Husseini, while speaking on Radio Berlin, passionately proclaimed: ‘Arabs, rise as one man and fight for your sacred rights. Kill the Jews wherever you find them. This pleases God, history, and religion. This saves your honour. God is with you.’

Hitler approved the publishing of an Arabic translation of Mein Kampf, and declared the (literally) blue-eyed Mufti an ‘honorary Aryan’, but never fully acceded to his requests. The Führer suspected, quite correctly, that Husseini was not nearly as influential as he claimed to be. Although widely supported in Palestine, Husseini certainly did not speak for all Arabs.

The legends about the keffiyeh tell that Palestinian Arab ‘rebels’ — supporters of Qassam and Husseini — wore the (black-and-white checkered) scarf during the 1936-39 revolt, to hide their faces and avoid arrest and punishment by the British authorities. Consequently, the colonial government outlawed the wearing of keffiyehs. But instead of obeying this British ordinance, all Palestinian Arab men adopted the keffiyeh, as an act of civil disobedience and solidarity. Thus, a symbol of resistance was born.

Almost none of this is true. In addition to numerous diaries and journalistic accounts, there are a great many photographs documenting the 1936 revolt and, while a few checkered keffiyehs can be seen (if you look closely enough — Where’s Wally? style), almost all were plain white. Indeed Arab rioters, loyal to Husseini, typically didn’t hide their identities. There are even photographs of large crowds of men, smiling at the camera as they raise their hands, and publicly pledge allegiance to the Mufti.

Most of the militant ‘rebels’ were fellaheen, from rural villages — men who would wear a keffiyeh and agal as a matter of course (not for anonymity, but to shield their heads from the sun). In August 1938, at the height of the uprising, the insurgent leadership commanded all townsmen to immediately stop wearing the tarboush (fez), and start wearing the keffiyeh and agal instead. Prior to this, the effendi (bourgeois Arabs of towns and cities), almost always wore the crimson-red Turkish tarboush — a hangover from Ottoman rule. By outlawing the wearing of the tarboush, the Arab leaders ensured that fellaheen militants would be far less conspicuous in urban settings.

A decade earlier, in 1929, there were a number of pogroms in Palestine, concentrated mostly in Hebron, Jerusalem, Safed, and Jaffa. Hundreds of Jews were injured or killed by Arab mobs, and huge amounts of Jewish land and property were destroyed. A formal enquiry into the anti-Jewish violence — led by the noted judge Sir Walter Shaw — resulted in an urgent recommendation that a new British criminal law be enacted to replace the Ottoman Penal Code, which was still in force in Palestine. From the earliest months of British control in Palestine, governors and jurists saw that the Ottoman laws were not fit for purpose, resolved to replace them, and then didn’t. There was much bureaucratic foot-dragging until the pogroms of 1929, when the relative permissiveness of the existing Ottoman laws (regarding homicide), allowed many of the Arab perpetrators to quite literally get away with murder. So in 1933 a new criminal code was drafted for Palestine and, after several more years of consultation and adjustment, it finally came into force in 1937. Chapter 33 (Burglary, Housebreaking and Similar Offences) of the Criminal Code Bill 1937, states that:

Any person who is found … having his face masked or blackened or being otherwise disguised, with intent to commit theft or a felony … is guilty of a misdemeanour.

Many of the activities of the ‘rebels’ were felonious, according to this new law. So, while it would have been illegal for a rioter to hide their face with a scarf, there was no law against wearing a keffiyeh per se. Characterising this legislation as some sort of colonial suppression of ancient Palestinian culture is patently absurd.

After 1939 the fellaheen continued to wear keffiyehs, as they had before the uprising. Whereas most effendi went back to wearing their old Ottoman-style headgear. Many citified and middle-class Arabs had resented being forced to wear keffiyehs, which they regarded as ‘peasant attire’, and therefore beneath them. They eagerly re-adopted the tarboush as a symbol of their class status.

It wasn’t until the late-1960s — when Yasser ‘Mr. Palestine’ Arafat began to gain worldwide notoriety — that the keffiyeh became a symbol of Palestinian nationalism. Regarding his birth, Arafat was quite open about the when (1929), but he consistently lied through his teeth about the where. When questioned about it he would usually say he was born in Jerusalem, at other times he said Gaza or Acre, though it is now well-known that he was born in Cairo. Two years before his birth, Arafat’s father, Abdel Raouf, moved his large family (Yasser was the sixth child) from their home in Gaza to a middle-class neighbourhood in Cairo. Although born and raised in Gaza, Abdel Raouf’s clan was Egyptian, and he believed that he was entitled to a considerable parcel of land in Egypt via maternal inheritance. This belief is reported to have become something of an obsession for him, and he spent twenty-five years pestering the Egyptian courts, though his efforts ultimately came to naught.

For Yasser Arafat, the keffiyeh did not represent his upbringing, it was an affectation. Born into a middle-class Egyptian home, he didn’t wear a keffiyeh growing up. In August 1956 Arafat, then an executive member of the GUPS (General Union of Palestinian Students), attended an international student conference in Prague. It was at this conference that he first adopted a (plain white) keffiyeh. Neither of his companions to the conference, who were also members of the GUPS, wore keffiyehs. But for Arafat it was an excellent PR stunt — he wore the headscarf while attending the sessions of the conference and, in so doing, stood out from the crowd. His motives are unknown; it may well be that he wore it as a symbol of the 1936 revolt, or to cultivate a more proletarian image, or simply to attract attention.

In 1957 Arafat moved to Kuwait, where he worked as a civil engineer. It was in Kuwait that he founded Fatah (today a political party, but then simply a Palestinian nationalist movement) in 1959. And it was at this point that Arafat began wearing the black-and-white fishnet keffiyeh that would become his trademark. He went on to develop a highly idiosyncratic way of wearing the scarf: draped over his head, and held with the traditional black cord, but folded so as to create a peak above the agal, and with the end hanging over his shoulder in a shape supposedly reminiscent of Palestine (as it appears on a map).

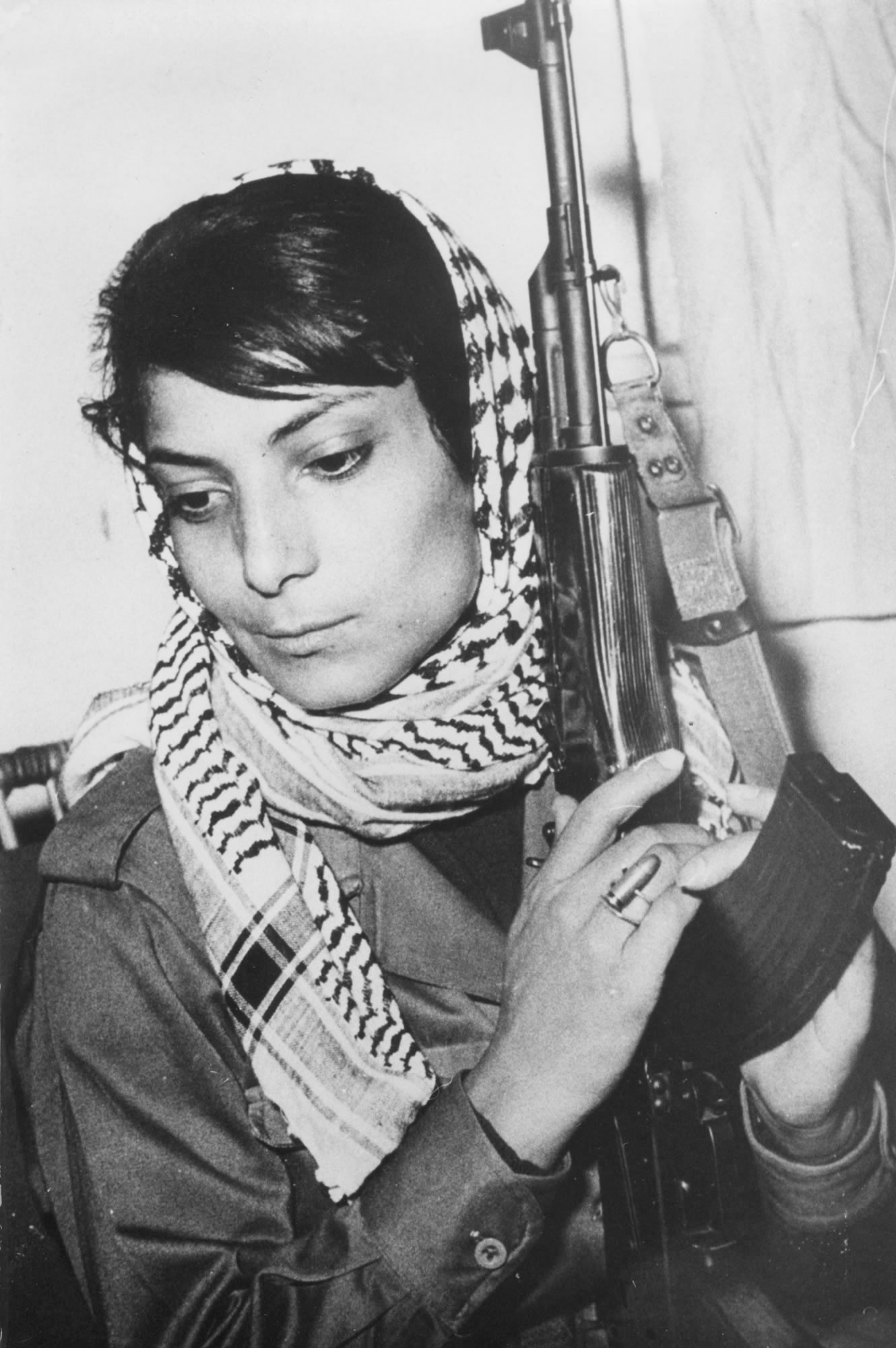

Following the establishment of the PLO (Palestine Liberation Organisation) in 1964, Arafat’s iconic style was widely emulated by Palestinian Arabs. By the time he ascended to the chairmanship of the PLO in 1969, the black-and-white keffiyeh was synonymous with the Palestinian cause. This association was further cemented by the international media’s fascination with PFLP militant Leila Khaled, who made history by becoming the first woman to hijack a plane. Khaled is often lauded as a heroine of female-empowerment, for her shattering of the terroristic glass ceiling. In one particularly iconic photograph Khaled wears a military-style jacket, a black-and-white fishnet keffiyeh, and a ring fashioned from a hand-grenade pin and a bullet — while holding a Kalashnikov assault rifle.

From the late-1960s onwards, the black-and-white ‘Arafat’ keffiyeh has been a symbol of the Palestinian cause. It is not known why Arafat adopted the pattern that he did — it may just have been the style most popular and readily available in Kuwait at the time — but the scarf’s design has retroactively been assigned all kinds of deep meaning. It is often claimed that the wide checkered pattern represents the nets of Gazan fishermen, that the secondary motif portrays olive branches (said to signify Palestinian strength and resilience), and that the thick grey bands running parallel to the edges symbolise the trade routes that ran through the ancient land. Of course, there is no documentary evidence to support any of this.

Literally, the word keffiyeh simply means ‘from’ or ‘in the style of’ Kufa — now a city in modern-day Iraq.

The July/August 2018 issue of Aramco World (an English-language magazine published in the US, and owned by the Saudi Arabian Oil Company) featured a delightful piece about the keffiyeh — authored by writer and documentarian Mariam Shahin, and featuring beautiful photography by George Azar. The article focuses primarily on the scarf’s popularity and influence in modern fashion and design, but also explores its history. According to Shahin:

The origin—and name—of the kufiya is said to go back to a battle between Arab and Persian tribes near the Iraqi city of Kufa in the early seventh century [CE]. Arab poet and historian Yousef Nasser recounts how before the battle, the Arabs wove headbands—’iqals—from camel hair to hold the plain headcloth in place so the Arab fighters would recognize their compatriots.

“After the battle,” Nasser says, “many of the Arabs took off their headdress, but they were told, ‘keep it on as a reminder of this victory until the end of time.’”

I strongly suspect this story is apocryphal. Any early 7th century battle between Arabs and Persians would almost certainly have been fought between the warring armies of the Muslim Rashidun Caliphate and the Zoroastrian Sassanid Empire, during the Muslim Conquest of Persia (633-654 CE). During this campaign, soldiers on both sides typically wore metal helmets, whose usefulness on a medieval battlefield is self-evident. Also, Middle Eastern headscarves, such a the Jewish sudra, are recorded long before the 7th century.

In Arab Dress, A Short History: from the Dawn of Islam to Modern Times, Yedida Stillman describes ‘a shawl-like headcloth which, though worn by Muslims, was considered a typically Khaybari Jewish garment.’ Anas ibn Malik, a sahabi (companion) of Muhammad, upon seeing Muslims at prayer wearing this shawl, was reported to have stated ‘[i]t seemed to me at that moment as if I were seeing Jews from Khaybar.’ Later, during the reign of Caliph Umar, the Jews of Khaybar were expelled from the oasis, and the formerly Jewish land there was used to construct barracks for Umar’s armies. As compensation, Umar gave the Khaybari Jews a tract of Land in Kufa, on the banks of the Euphrates. Make of this what you will.

Modern keffiyehs come in a variety of colours, weights, and patterns — some more traditional than others — and are referred to by many different names. In Palestine keffiyeh is almost always used, especially for scarves decorated with the now iconic black-and-white fishnet pattern. The red-and-white Jordanian version, often decorated with a tight check, similar to houndstooth, and woven from heavier yarn (à la Glubb), is usually called a shemagh. Elsewhere in the Levant, hattah is popular, while in the Arabian Peninsula the headcloth is best known as a ghutra. Persians and Kurds generally use the terms chafiyeh, and serwîn, respectively. And, for an increasing number of Jews, both in Israel and the diaspora, the name sudra is being revived.

In 2009 a man named Boruch Chertok designed a woven cotton scarf. It was about a metre square, with fringes along its edges, and was decorated with a tessellated Star of David pattern in a beautiful blue-and-white palette, reminiscent of ancient tzitzit. Chertok teamed up with Yemenite-Ashkenazi Jewish DJ Erez Safar (better known by his stage name, Diwon), to produce and sell the scarf, which was initially marketed as an ‘Israeli keffiyeh’.

This was an act of ethnic decolonisation — a tangible way for Chertok and Safar to express their Jewish pride, and reconnect with the pre-Islamic Levantine culture that is their birthright. A culture that is the birthright of all Jews. But it was not seen as such by Arabs in general, and Palestinians in particular, who accused the pair of ‘cultural appropriation’, or even ‘cultural genocide’.

Shadia Mansour, a British-born Palestinian hip-hop artist, was outraged that two American-born Jews had the chutzpah to ‘steal’ this ‘ancient’ symbol of her Palestinian heritage. She quickly released a protest record — a furious Arabic-language rap entitled Al Kufiya Arabiya (The Keffiyeh is Arab).

I am not an Arabic speaker, but I was able to find an English translation of the lyrics, courtesy of the Brooklyn Academy of Music. The poem is dripping with antisemitic imagery. It refers to to Jews as ‘dogs’, alludes to our wanting to be served ‘Arab blood or tears’, and suggests that we should learn ‘how to be human before [we] wear [their] scarf’. The song speaks of Jews wanting to ‘steal’ the ‘dignity’ and ‘intellect’ of Arabs. And heavily implies Jewish greed — ‘they imitate our style, as if all this land is not enough’. Below is an excerpt from Mansour’s lyrics:

Dogs of the past [are] starting to wear it as a fashion statement

However they change it, whatever color they make it

The kufeyyeh is Arab, and it stays Arab

Our scarf, they want it

Our dignity, they want it

Our intellect, they want it

Everything ours, they want it

We will not be silent, will not allow it

It suits them to steal something that ain’t theirs

They imitate our style

As if all this land is not enough

Know how to be human

Before you wear our scarf

I would be remiss if I didn’t point out that ‘all this land’ (The State of Israel), is equal to approximately 0.17% of the lands controlled by The Arab League, of which the State of Palestine is a member.

While they are deeply antisemitic, I believe that Shadia Mansour’s lyrics are rooted in ignorance — not conscious, sincere, Jew-hatred. The same is probably true of American rapper Mutulu Olugbala (stage name M1), who collaborated with Mansour on the track, and contributed the following English-language lines to the song:

I’m pro-Falastini, does that make me a terrorist?

You can catch me in Gaza, Haifa or Ramallah

But I’m still just Mutulu Olugbala

So when I rep with Shadia

We rhyme with our middle fingers up to the Zionists

Because we don’t give a fuck, it’s justice

Lavonne Alford, from New York City, adopted the name Mutulu Olugbala in the 1990s. As many Black Americans had done before him, he dropped his diasporic name, and adopted an African one instead. Diaspora Jews have always had Hebrew names, but their use was generally limited to religious services, synagogue records, memorial rituals, and gravestones. Like Alford, Zionist pioneers such as lexicographer Eliezer Ben-Yehuda (born Eliezer Yitzhak Perlman) also chose to discard the names of their exile, and proudly adopt Hebrew names for daily use.

Many African-Americans, especially in the Jim Crow south, grew up eating ‘soul food’, and wearing the European-style clothes popular in the United States. But, during the Civil Rights and Black Power movements of the 1960s, some African-Americans sought to reconnect with their African heritage — donning traditional West African garments, and exploring West African cuisine. Surely it is not inappropriate for Black Americans, descended from enslaved Africans, to feel an affinity with jollof rice or egusi stew. Likewise, the existence of classic Yiddish dishes, such as gefilte fish and kreplach — the ‘soul food’ of Ashkenazi Jewry — does not invalidate our connection to Levantine cookery. I would also argue that the keffiyeh/sudra belongs to me, a diaspora Jew, no less than the dashiki belongs to African-Americans.

I’m not African-American. I’m not going to tell African-Americans what to say or think, or dictate to them how they are permitted to express their identities. I would humbly ask that Mutulu Olugbala show me the same respect, instead of sticking his ‘middle finger up’ to Zionism — the emancipation and national liberation movement of the Jewish People.

In 1961 Yasser Hirbawi bought some second-hand Suzuki looms, and opened a small textile factory in Hebron. The factory is often touted as the ‘last keffiyeh factory in Palestine’. It is certainly the only keffiyeh factory in Palestine today, but I suspect it may also be the first. The official British government Handbook of Palestine and Trans-Jordan (1930), explains that the ‘weaving of … Arab cloths and headgear’ was one of the traditional handicrafts in Palestine. However, such manufacture was done on a small, local scale. The handbook goes on to state:

About the year 1924 [Jewish] immigrants from Poland, particularly from Lodz, began to arrive, bringing with them a wide knowledge of the textile trade and the necessary machinery. Small textile factories were started, of which the principal is the Lodzia Factory, chiefly engaged in the manufacture of stockings

Although Arabs (and Jews) had been making textiles in Palestine for generations, it was not until an influx of Zionist immigrants arrived from Lodz — then one of Europe’s biggest producers of textiles — that factories like Hirbawi’s began to appear. Perhaps Yasser Hirbawi himself, or his father, learnt to operate industrial looms under the tutelage of Polish-born Jews! I can find no record of any keffiyeh factories in Palestine between 1930 and 1961. The scarves seem to have typically been imported from Syria during this period.

After Arafat made it famous, the keffiyeh’s popularity among activists grew, and so did demand for the checkered scarf. The Hirbawis are amply equipped to supply this demand, but have struggled to compete with the absurdly low prices of Chinese-made keffiyehs. The latter are mass-produced on an enormous scale, are poorly-made, feature patterns that are usually printed rather than woven, and usually retail at less than £5.

Yasser Hirbawi died in 2018, but his factory is still very much a family business; today it is managed by his three sons. In addition to the classic ‘Arafat’, the factory produces a wide variety of sumptuously coloured modern keffiyehs, decorated with beautifully woven Jacquard patterns.

Although I will never wear an ‘Arafat’, I personally own a growing collection of Hirbawi scarves. I’m very proud to support Palestinian artisans, help the economy of the West Bank, and also to wear a beautiful keffiyeh/sudra woven in the holy city of Hebron. To me, the scarf is an expression of my own Middle Eastern ancestry, and a connection to the past. It says to the world that, despite centuries of exile and persecution, we Jews have not forgotten our roots.

Sadly, I image that if I had spoken to Mr. Hirbawi before his passing, or if I were to speak with his sons today, they would take exception to my referring to their scarf as a sudra, although it is essentially just the traditional Jewish name for the same garment. I also suspect that they would disagree with my belief in the inherent legitimacy and justice of a sovereign Jewish state within the historic regions of Judea, Samaria, and the Galilee.

Regardless, if any readers would like to join me in supporting the Hirbawi factory, please make sure to order from their official website, as there are many counterfeit Hirbawi scarves on the market.

When Shadia Mansour performed Al Kufiya Arabiya to a live audience in New York City, she proclaimed ‘[y]ou can take my falafel and hummus, but don’t fucking touch my keffiyeh!’

Young firebrand Arabs like Mansour regard the scarf as exclusively theirs. But they should remember that — at its height under the Umayyad Dynasty (661–750 CE) — the Arabic empire encompassed not only the Levant, but also most of North Africa, nearly all of the Iberian Peninsula, and large parts of the Indian subcontinent, Central Asia, and the Caucasus — over eleven million square kilometres of land. The peoples whom the Arabs conquered invariably had their languages, religions, and cultures erased or subsumed. Just as Britons cannot claim ownership of Assam tea, chicken tikka masala, or Madras cotton, Arabs cannot claim sole ownership of the keffiyeh.

Both the keffiyeh and the sudra are simple woven scarves, likely of similar dimensions, that have been decorated in a variety of ways over the centuries. They can be used to protect one’s head and neck from the sun; shield one’s face from wind, dust, and sand; and warm oneself in colder months or at night. Because of their practicality and versatility, they have been part of the vestiary landscape of the Middle East and North Africa for millennia — certainly long before 7th century Muslim conquerors violently paved the way for the Arab hegemony in the region today.

We know that Arabs have, at times, emulated and appropriated Jewish styles, while simultaneously banning Jews from wearing them. It is certainly possible, perhaps likely, that the checkered patterns of modern keffiyehs have their origins in ancient, or even medieval, Jewish fashions. Sadly it is impossible to know for certain, as classical Jewish culture has been so thoroughly eroded by centuries of ‘dhimmitude’ under Muslim conquerors.

After fourteen centuries of Arabs governing Jewish wardrobes, it is unspeakably inappropriate (not to mention the height of irony) for them to cry foul when a Jew chooses to design or wear a sudra/keffiyeh today.

So nu, who is erasing whose history?

Aburish, S.K., (1998) Arafat: From Defender to Dictator

Adler, M.N., ed. (1904) The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela

Bensoussan, G. (2019) Jews in Arab Countries: The Great Uprooting

Bentwich, N. (1938) Journal of Comparative Legislation and International Law, Vol. 20, No. 1

Blady, K. (2000) Jewish Communities in Exotic Places

David, A. (1999) To Come to the Land: Immigration and Settlement in 16th-Century Eretz-Israel

Garnett, D., ed. (1938) The Letters of T.E. Lawrence

Gilbert, M. (2010) In Ishmael's House: A History of Jews in Muslim Lands

Graetz, H., (1894) History of the Jews, Vol. 3

Hourani, A. (1991) A History of the Arab Peoples

Julius, L. (2018) Uprooted: How 3000 Years of Jewish Civilisation in the Arab World Vanished Overnight

Karsh, E. (2007) Islamic Imperialism: A History

Lewis, B. (1984) The Jews of Islam

Luke, H.C., ed., and Keith-Roach, E., ed. (1930) The Handbook of Palestine and Trans-Jordan

Massad, J. (2001) Colonial Effects: The Making of National Identity in Jordan

Milton-Edwards, B. (1999) Islamic Politics in Palestine

Roseberry, W., ed. and O'Brien, J., ed. (1991) Golden Ages, Dark Ages: Imagining the Past in Anthropology and History

Rubinstein, D. (1995) The Mystery of Arafat

Shulewitz, M.L., ed. (1999) The Forgotten Millions: The Modern Jewish Exodus from Arab Lands

Stillman, Y.K., and Stillman, N., ed. (2000) Arab Dress, a Short History: From the Dawn of Islam to Modern Times

Tobi, Y. (1999) The Jews of Yemen: Studies in their History and Culture

Yaghoubian, D., ed. and Burke, E., ed. (2005) Struggle and Survival in the Modern Middle East

Yedid, R., ed. and Bar-Maoz, D., ed. (2018) Ascending the Palm Tree: An Anthology of the Yemenite Jewish Heritage